Announcing the ClassID series

When you get into Flesh and Blood (or any card game for that matter), the first question you are faced with is which deck you are going to play. Perhaps this question is easier to answer in Flesh and Blood than in some other games because you can just make your decision based on the vibes you get from each hero. However, you could give your decision quite a bit more thought, if you are so inclined, by considering their mechanical design. Whilst at a glance you might consider a hero’s ability their single most defining feature, I would argue it is actually their class (or perhaps their talent-class combination). That is because classes in Flesh and Blood have an extremely strong identity and design philosophy, and their ability is informed by the strengths of the class cards to which they have access. Hence, I am launching a series of articles, which I have dubbed ClassID, to take some time to look at each class’s design, and how heroes within a class differ (wow, do they differ wildly sometimes). In this introductory article, I will outline how I will be characterising classes in this series, and explain my reasoning behind this methodology.

Note: This series is a departure from the other content on this blog. I will not move away from the other articles, merely alternate them with this series.

Class design

What makes the hero design in Flesh and Blood so great is that each hero feels distinct and unique. However, within each class heroes typically share some characteristics, though talents can shake things up quite significantly. Take for example Dorinthea and Kassai. For both talentless heroes (don’t call them that to their face) it is immediately clear from their hero ability that they care about weapon attacks. This is because the reliance on their weapon is perhaps the most important trait of the Warrior class. When a talent is added to the class though, like in Boltyn’s case, the playstyle is shaken up profoundly. Though the Light Warrior has access to a large collection of attack actions (which the untalented Warrior pool lacks, aside from hybrid cards, i.e. cards playable in more than one class), it is evident from his signature weapon, Raydn, that he is incentivised to swing his weapon as often as possible, since 0-for-3 is such a great rate.

Each class has defining traits that are unique to that class, like Warriors relying on weapon attacks to push damage through turn after turn. This is exactly why I could (and will) write an article about each class. Aside from their uniquely defining play patterns, there are a few general characteristics that can be quantified for each class as well though. Let’s see how we can distill some class identity into a few key concepts.

General design concepts

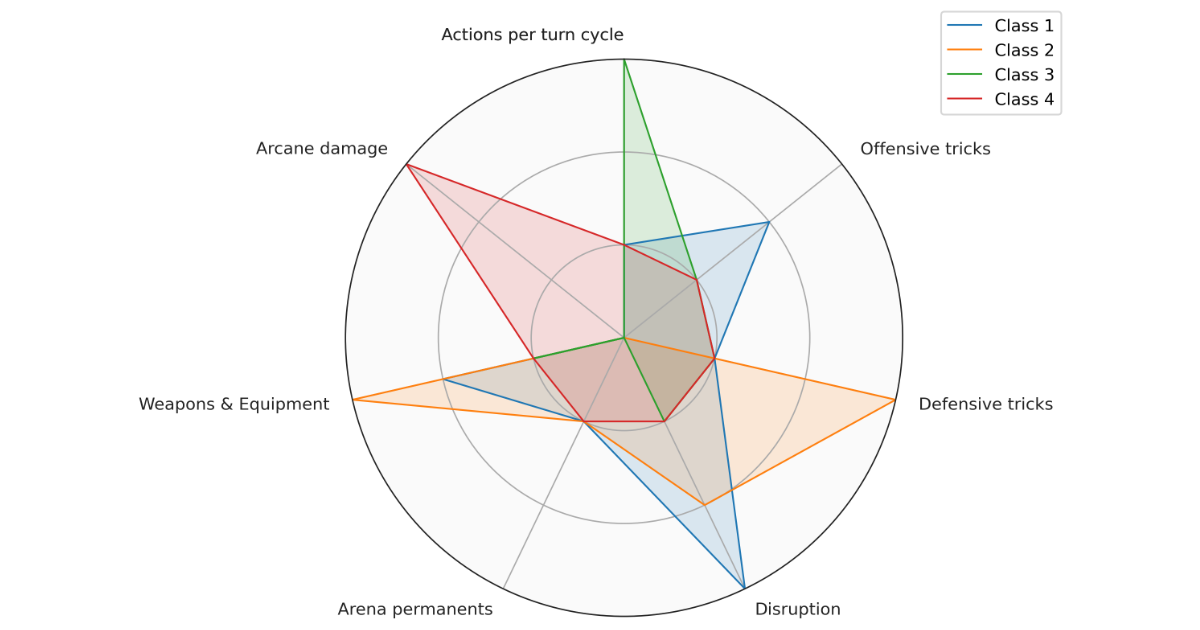

Each class has some design concepts that are unique to that class, but there are also a few concepts that can be quantified across the board. Whilst I can think of several more, I am limiting myself in this series to seven concepts: actions per turn cycle, offensive combat tricks, defensive combat tricks, disruption, arena permanents, weapons and equipment, and arcane damage. Though most concepts probably speak for themselves, allow me to elaborate and highlight why I chose these key concepts as my general metric.

Actions per turn cycle

The first concept is how many (offensive) actions a class generally takes on any given turn cycle (per turn cycle because Wizards exist). Think e.g. of Guardians vs Ninjas. Guardians are the strongmen that combine all their might in a single blow whilst Ninjas chain together several smaller attacks. Thus Guardians score low on this concept whilst Ninjas score high. In my eyes, this concept is one of the most important ones for a class’s identity because it ties into a turn’s flexibility or modularity, if you will. A Ninja is quite flexible in how many cards they want to dedicate to offence versus defence, whilst a Guardian generally has to commit their whole hand if they want to do something more impactful or flashy than swinging their weapon.

Offensive and defensive tricks

Since some classes do not get any (or extremely limited amounts of) attack or defence reactions within their class pool, these metrics speak for themselves. If a class has no attack reactions in their class pool, like Guardian, they will score low on offensive tricks compared to the Warrior class, which has lots of attack reactions. However, these categories are not limited to reaction cards. A few classes feature combat tricks of the instant type (looking at you, Illusionist) or perhaps on their equipment. Hence, we use these more general descriptors to indicate how many options a class has in the reaction phase of an attack, on the attacking and defending side separately.

Disruption

At first I considered calling this category “on-hit effects”. Brutes have few on-hit effects whilst Assassins have many on their contract cards. However, the Ninja class made me reconsider this because they have quite a few on-hit effects, but very few of them actively disrupt what the opponent is trying to do. And that is what I want this category to be about: how much do you have to play around your opponent’s cards and effects? Brutes are mostly just numbers and don’t really force their opponent to adapt their gameplan (generally speaking) whilst most people will agree that facing an Assassin does make them consider alternative lines of play.

Arena permanents

I will summarise this characteristic in three words, irrespective of the purpose they serve in the class’s gameplay: items, auras, allies. In practice, this characteristic quantifies a class’s ability to carry over value from one turn to the next beyond the arsenal.

Weapons & Equipment

Though the Generic card pool has quite a few great equipment pieces, it only contains a single weapon at the time of writing. And this is good because weapons and equipment are an integral part of a class’s feel. A Ninja is flexible and agile, and should thus wear light armour and rely on quick and small weapon strikes. Hence, the class features mostly equipment pieces with low defence values and blade break, i.e. they block once and are gone. Warriors on the other hand don the finest platemail they can find and have a true “fridge” of armour, as the community likes to call it. Furthermore, their weapons feature great numbers at low costs (mostly). In this metric I will combine the overall quality of weapons and equipment. Regarding equipment, I will mostly refer to their defensive capabilities, but note other aspects in the full discussion.

Arcane Damage

Finally, I chose to add arcane damage to the list. Though most classes don’t have access to arcane damage, those that do are strongly defined by it and by how much arcane power they wield.

Radar charts

In future articles in this series, I will assign each class a value for each of these categories, ranging from 0 to 3, with 0 reflecting no (or extremely limited) access to this feature and 3 identifying it as one of the class’s core strengths. All seven values can then be summarised in a radar (or spider) chart, such as the one on the top of this page. Can you guess which classes these four charts represent?

What’s next?

Starting next week, I will be diving into each class one by one, grading them in each of the seven categories outlined above, and highlighting which complimentary design principles or features the class adheres to. My hope is that this will be a useful resource to some of you, and I am already curious to see how these articles will age as more heroes are introduced for each class. Currently, I don’t have any particular order in mind, so please let me know which class you would like to see first!